Classical Art and Atlantic Slavery

Gavin Hamilton’s James Dawkins and Robert Wood Discovering the Ruins of Palmyra (1758), today in Edinburgh, is a good place to start thinking about the relationship between classical art and Atlantic slavery.

The painting depicts James Dawkins II and Robert Wood, the two men dressed in togas, as they round a corner towards a ruined street and arch in ancient Palmyra. James Dawkins funded both the expedition here commemorated, and Wood's Palmyra (1753), the resulting "elephant folio" that initiated widespread distribution and imitation of images of classical architecture in Europe.

Dawkins also hosted James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, whom he and Wood had met on their travels, in his London house while they prepared their Antiquities of Athens (1762).

When James Dawkins died in 1757, his brother Henry commissioned this canvas from the Scottish painter Gavin Hamilton, himself a prominent excavator of and dealer in classical sculpture.

Where did the Dawkins brothers get their money? They held joint title to some 25,000 acres of sugar plantation in Jamaica, and a commensurate number of slaves. In 1835 and 1836, following Emancipation, the trustees of Henry's son, James Colyear Dawkins, claimed "compensation" for 724 enslaved people, receiving an award from Parliament of some thirteen thousand pounds (well over a million in today's terms).

Therefore, the production and dissemination of an enduring idea of classical art was funded by a brutal regime of race-based slavery in the British West Indies. Should this make us reconsider the figure tending the horse at the right of Hamilton's painting?

As for the animal, one thinks first of Dr. Johnson’s aperçu: "The only great instance that I have ever known of the enjoyment of wealth was that of Jamaica Dawkins, who going to visit Palmyra, and hearing that the way was infested with robbers, hired a troop of Turkish horse to guard him."

As for the man, his dress codes him as Ottoman, his physiognomy and skin color as African. Of all the figures in the painting he stands furthest in the foreground and wears the brightest blues and reds.

Why can African labor appear plainly in a painting of the British invention of classical art, so long as the African is shown as an Ottoman subject? A related question arises from The Greek Slave (1843) by Hiram Powers.

She is doubly Greek: Greek as a Greek statue, but also Greek as an Ottoman subject. Writes the sculptor:

"The Slave has been taken from one of the Greek Islands by the Turks, in the time of the Greek Revolution; the history of which is familiar to all. Her father and mother, and perhaps all her kindred, have been destroyed by her foes, and she alone preserved as a treasure too valuable to be thrown away. She is now among barbarian strangers, under the pressure of a full recollection of the calamitous events which have brought her to her present state; and she stands exposed to the gaze of the people she abhors, and awaits her fate with intense anxiety, tempered indeed by the support of her reliance upon the goodness of God. Gather all these afflictions together, and add to them the fortitude and resignation of a Christian, and no room will be left for shame."

Here she is exposed to the gaze of respectable people and without shame:

After British Emancipation, but while Americans still owned slaves, slavery can appear as barbarous to public view, so long as the slave is both classical and Christian, and the tyrant is a Turk.

Atlantic slavery is very much present in classical art, refracted through the Orient.

--

Hamilton’s Dawkins and Wood is a bit embarassing. It is a bit over the top.

That willowy palm is a bit too distressed, that mustachioed Turk a bit too sinister, the black man a bit too black.

Who is he in this picture? How did he end up here?

Is he a caricature, like the leftmost figure in Hogarth’s Taste in High Life (1746); this latter, “an enslaved servant who wears an exoticizing feather turban, pearl earring, and metal collar”?

Dawkins and Wood were not wearing togas when they reached the ruins at Palmyra, but they were accompanied by Arab riders; perhaps also an African man?

Dawkins and Wood were not wearing togas when they reached the ruins at Palmyra, but they were accompanied by Arab riders; perhaps also an African man?“We set out from Hassia the 11th of March 1751,” writes Wood, “with an escort of the Aga’s best Arab horsemen, armed with guns and long pikes, and travelled in four hours to Sudud, through a barren plain, scarce affording a little browsing to antilopes, of which we saw a great number.”

Eventually the caravan “encreased to about two hundred persons, and about the same number of beasts for carriage, consisting of an odd mixture of horses, camels, mules and asses.” The horsemen of the “Arab guard” “always rode off from the caravan at full speed, in the Tartar and Hussar manner.” Sometimes “they “engaged in mock fights with each other for our entertainment, and shewed a surprising firmess of feat, and dexterity in the management of their horses.” At night, there was coffee, tobacco, and the recitation of “a song or story, the subject love, or war, and the composition sometimes extemporary.”

Coffee and tobacco tie together Louis-Francois Cassas’s view, published in 1800, of his own arrival in Palmyra, 1785:

This resembles Wood’s description. It is also certainly closer to the truth of an antiquarian’s arrival in Palmyra than Hamilton’s painting: Cassas and Wood were there, Hamilton was not. (The artist who accompanied Dawkins and Wood, Giovanni Battista Borra, did not produce an image of arrival.)

This resembles Wood’s description. It is also certainly closer to the truth of an antiquarian’s arrival in Palmyra than Hamilton’s painting: Cassas and Wood were there, Hamilton was not. (The artist who accompanied Dawkins and Wood, Giovanni Battista Borra, did not produce an image of arrival.) Hamilton has to make up his image by assembling bits out of Wood’s volume, and other bits out of his imagination. Since the African man doesn’t come from Wood’s account, Hamilton has probably imported him from somewhere else.

--

Where is classical art in Hamilton’s picture?

Palmyra, for scholars today, belongs firmly to “Roman Syria”; peripheral, hybrid. It is not the obvious place to discover classical art. And yet Dawkins and Wood, and Hamilton in their train, do just that.

The classical art that glows blue pink and yellow at picture left is quoted from Wood’s Palmyra:

The view of colonnades converging on both sides of the central arch suggests itself. John Henry Haynes made a closer version with a camera in 1885, with fewer standing columns:

The view of colonnades converging on both sides of the central arch suggests itself. John Henry Haynes made a closer version with a camera in 1885, with fewer standing columns:

Hamilton dresses it up, adding a second low arch to the left of the central one. Here in the print of his painting:

In the print, the second piece of antiquity is more readily legible than in the painting: the carved human figure, a cushion under its head, who lies upon a plinth placed atop brackets, which themselves are built into a masonry tower. It too comes from Wood:

The text in the engraving is blank; that on the painting has been borrowed from the second in Wood’s collection of Palmyrene inscriptions:

Wood comments: “II. Upon the front of that Mausoleum [See Plate LV. LVI. LVII.] of which we have given the plan, elevation and ornaments. Besides that we found no difficulty in reading it, both grammar and sense so evidently authorise the difference of this copy from that already published, the we shall not trouble the reader with any defence of it.”

For the antiquarian the sense is self-evident, and the painter seems to have followed it, even if the low contrast makes it hard to read:

The engraving, by contrast, makes a jumble of it, misreading letters and adding new ones to fill out the lines:

What of the man who confronts the inscription? Wood writes: “We are at a loss whether to attribute so much bad spelling, and different ways of spelling the same word, as may be observed in these inscriptions, to the mistakes of the engraver or to their ignorance of the Greek language at Palmyra. Longinus complains that he found it difficult to find a person there to copy Greek.”

The right side of the picture is the dark side. In the tower’s shadows a turbaned man puzzles at a faint inscription in bad Greek. We are a long way from Wood’s university days in Glasgow.

The left side is the bright side. Here a spruced-up patch of monumental architecture beckons two fresh Romans and a handsome torso:

Thus Hamilton distills classical art out of Palmyra’s mash.

--

Which man is which? One scholar writes: “the figure behind Wood is the artist/architect who accompanied the party, G. B. Borra.” Thus, from left to right: Dawkins leads pointing, Wood gazes admiring, Borra draws.

Wood’s face - a bit pinched, nose less Roman than his companion’s - we can now recognize from solo portraits by Anton Mengs and Allan Ramsay. For Dawkins, on the other hand, Hamilton’s painting and the plate in Stuart and Revett are the only two portraits we possess, and both are doubles.

The plate, says Stuart, is “a view of [the Monument of Philopappos, in Athens] in its present state. On the foreground Mr. Revett and myself are introduced with our friends Mr. James Dawkins and Mr. Robert Wood; the last of whom is occupied in copying the inscription on the pilaster. Our Janizary is making coffee, which we drank here; the boy, sitting down with his hand in a basket, attends with our cups and saucers. A goatherd with his goats and dogs are also represented.”

Stuart and Revett in local garb, mustachioed; Dawkins and Wood dressed as Englishmen, bare-lipped; the herder’s staff a neat parallel to Dawkins’s stick. Wood stands at a distance from the inscriptions, Greek and Latin, that relate the career and titles of C. Julius Anitochus Epiphanes Philopappus, “grandson of the last king of Syrian Commagene.” Even in Athens it is hard to escape Syria.

The plate gives us a lot. It gives us a very different view of fieldwork than Hamilton’s painting, a chattier and more casual exchange, goats and dogs instead of horse and camel. Like Cassas, it gives us coffee. But it doesn’t lend much physiognomy to Wood or Dawkins.

Which man is which? The engraving of Hamilton’s painting reads “Dawkins and Wood,” left to right, roughly beneath the two men’s feet:

Alphabetical, and also a reflection of status: he who pays takes the first step. Here is Wood writing as “The Publisher to the Reader”:

“If the following specimen of our joint labours should in any degree satisfy publick curiosity, and rescue from oblivion the magnificence of Palmyra, it is owing entirely to this gentleman [i.e., Dawkins], who was so indefatigable in his attention to see every thing done accurately, that there is scarce a measure in this work which he did not take himself.

“At the same time that, by this declaration, I disclaim any share of merit which the publick, uninformed of the truth, might have given me, I cannot help in return indulging my vanity with a circumstance, which I am sure does me honour, viz. that my being the publisher of these sheets is owing to Mr. Dawkins his friendship for me, who while he highly enjoys the pleasure of contributing to the advancement of arts in this manner, declines the profits which may arise from this publication.

“If I venture to mention this single instance of my friend’s regard for me, I shall compound with him for that liberty, by suppressing others without number: To join Mr. Dawkins’ name with mine (where I must still continue to be the only gainer) is, I fear, little less than impertinent, but it is the impertinence of gratitude, which, like love, is never more aukward in it’s declarations than when it is most sincere and in earnest.”

--

Dawkins, in Hamilton’s painting, is a bit blonder than Wood. In this group of men he is the prettiest, a man in his mid-20s. His collarbone braces a tasteful decolletage.

It is a chaste scene. Wood looks a decade older than Dawkins (in truth five years), and bonier. His gesture of demure amazement reads, appropriately, as Protestant (his father was a minister in Ireland). Only Borra, if that is Borra, suggests a bit of Orientalist reverie. (He appears without name in Wood’s Palmyra as “a fourth person in Italy, whose abilities as an architect and draftsman we were acquainted with”).

It is strange to arrive at the juncture of classical art and Atlantic slavery and find - no sex. But this too finds a parallel in the Protestantism of Hiram Powers’s Greek Slave.

“Naked yet clothed with chastity,” poetized an American, “She stands”:

And as a shield throws back the sun’s hot rays,

Her modest mien repels each vulgar gaze.

Her inborn soul of purity demands

Freedom from touch of sacrilegious hands,

And homage of pure thoughts.

Greek art was by definition full of sex. Winckelmann, a few years after Hamilton painted his picture, traces the muscles of the Belvedere Torso as one falls into another, “and our glance is, as it were, likewise swallowed.”

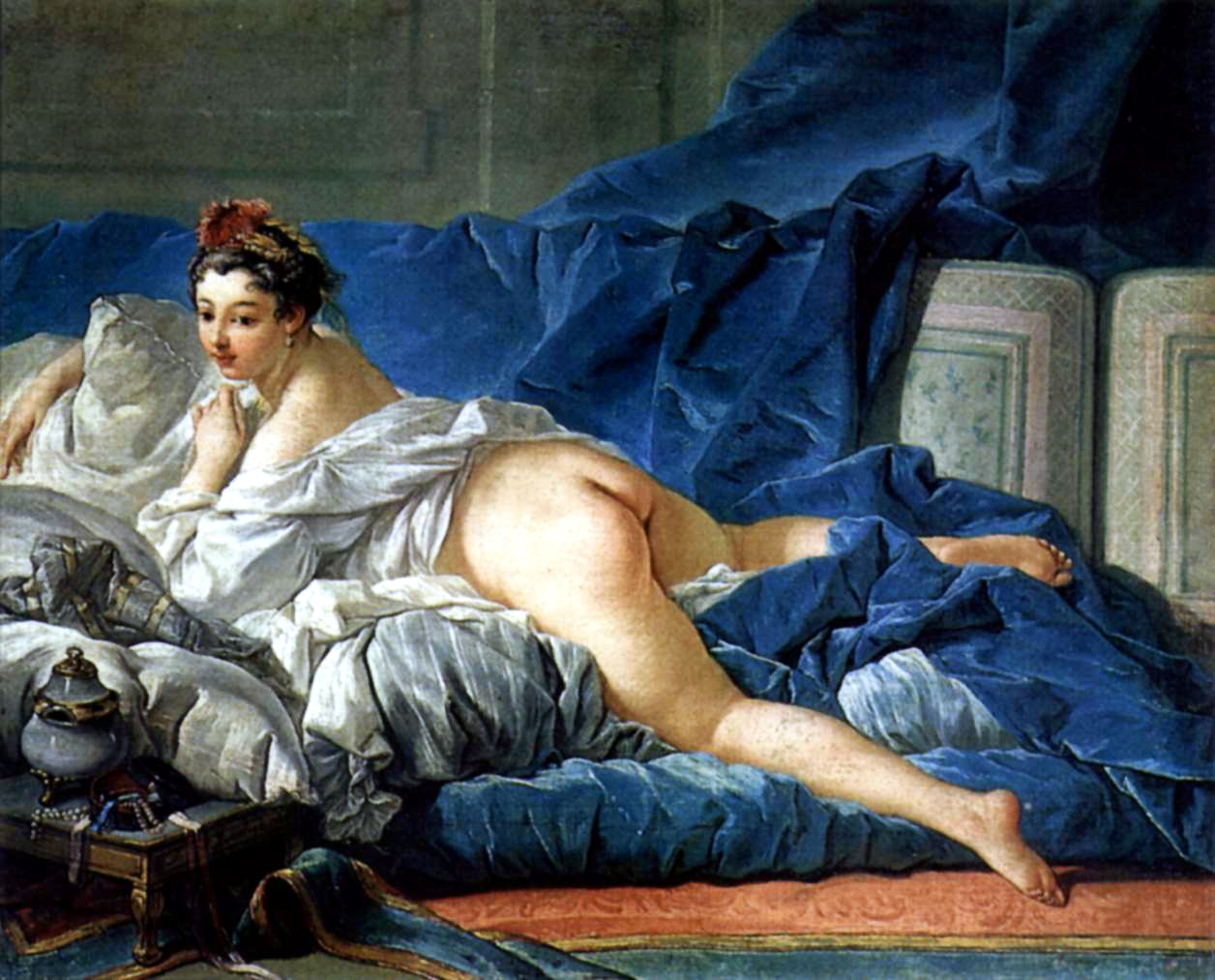

The Orient, also by definition, was also full of sex. “Odalisque” - the term a kind of pidgin Turkish - named “the eroticized artistic genre in which a nominally eastern woman lies on her side on display for the spectator.” Or on her stomach, as in a picture by François Boucher from the 1740s:

Atlantic slavery is different. In reality it wallowed in the cruellest manipulations of flesh. While Dawkins and Wood traveled in the Orient, in Jamaica an English overseer (not of Dawkins’s plantations, but of similar), Thomas Thistlewood, recorded minutely, often in Latin, his daily rapes and tortures of enslaved Africans.

By contrast, the visual code that governed relationships of “masters” to “slaves” enforced chastity. Thus a portrait by Bartholomew Dandridge, in which a collared dog and collared man adore a young girl, plays off the pagan grisaille: “The relief on the urn, which shows a group of cherubs taming a wild goat—an allegory of carnal lust—serves as a contrast to the ostensibly chaste, ‘domesticated’ love, which the young girl is shown to inspire in her two attendants.”

Dandridge’s portrait is monstrously fascinating. The girl’s gaze petrifies. Hamilton’s painting is not pulled as taut, but the two are nonetheless kin. The African man alongside Dawkins and Wood carries something of that absolute chastity. He domesticates the scene. He holds the reins.

For me, Hamilton’s depiction of the black man renders explicit the scene’s depravity, the reliance of the project that it promotes on a morally repugnant regime of race-based slavery. But for Hamilton, or for another early viewer of the picture, that same figure helps to purify the scene, to maintain the strict distinction between the oriental and the classical through which both become respectable.

--

One can think of this as an art (oil painting) bent to serve an ideology (eighteenth-century empire, white supremacy). But one can also see it as that art doing precisely what it did best. Writes Berger: “The claim of universal democracy was inadmissible for oil painting.” Oil paintings - the kind with glowing horizons, and perspectival constructions - set up comparisons, not equivalences.

There is nothing of ancient Greece or Rome in an oil painting: nothing about the oils themselves, and nothing about the conventions that structure the depiction. There is, for example, no equivalent in Greek or Roman mural painting to the convention (hierarchy of genre) that dresses Dawkins and Wood in togas.

Hamilton’s painting is classical art, as distinct from ancient Greek or Roman art. Ancient art is just part of the mix out of which classical art is made. Atlantic slavery and Orientalism are present in equal measure.

--

How does it work with sculpture? Here is The Greek Slave in the form I have shown thus far, a plaster cast of the clay mold made by Powers:

And here as she toured, in one of six marble statues executed by professional carvers under Powers’s direction:

What does the shift in color, from yellow-brown to mirror-white, do?

The plaster looks ancient: the material Etruscan, the surface oddly like a fine Roman bronze.

The marble looks classical: by which one could almost say, kitsch. The polish points this way, as do the manacles. The cross and tassles are on the cast intriguingly worn, but on the statue they shout like stage props.

Thus the “classical” in the marble statue does not derive from ancient Greece and Rome alone. Here too, as in Hamilton’s painting, it is an admixture: of ancient art, yes, but also of Orientalism and Atlantic slavery. The difference is that an oil painting could never be ancient, but many marble statues are. There are potential analogues to Powers’s sculpture, of a kind that do not exist for Hamilton’s painting.

The ancient model is the Aphrodite of Knidos:

The strut is built from a water vase and a garment; she is bathing, and you have surprised her, or she doesn’t see you, no matter. In either case the narrative is immediate, it is about her and you.

Powers will have seen her in Rome, as above; and another version, differently strutted, in Florence. By a happy coincidence, a copy of the latter (the “Venus de Medici”) appears today in Edinburgh alongside Hamilton’s Dawkins and Wood.

Powers literalizes the strut. In the ancient statue, the strut helps the marble to stand, but the garment is not understood to support Venus’s weight. By contrast, in Powers’s statue, both marble and woman rest on the draped post.

The change allows a shift in posture. The hand that connects to the strut is no longer compelled to hold up the cloth, and thus can be placed lower; as a result, Powers can arrange the chains as if a slight veil.

These conjoint adjustments turn a Greek goddess into a Greek slave. The manacles signify her unfreedom; the cap and tasseled robe present as eastern dress; the cross as Christian. These devices cluster about her sex, while simultaneously rendering her chaste: the chains through visual interposition, the cross through spiritual prophylaxis.

Even without Powers’s text, then, his statue places its viewers in a specific narrative context. The effect is entirely different to that of the ancient statue, in which only the figure’s perfection establishes her divinity.

Many have found the Aphrodite of Knidos proper: for example, the Scottish surgeon John Bell, dying in Rome ca. 1820, remarked upon her “character of modesty singularly pleasing.” But the statue’s history is also one of defilement. Already in antiquity a “young man of distinguished family” left “behind one of the thighs a stain.” In Portrait of the Artist, Stephen’s friend Lynch admits: “one day I wrote my name in pencil on the backside of the Venus of Praxiteles in the Museum.”

If Powers’s sculpture admits no equivalent, this owes largely to the narrative context that pose and attribute produce. It defines its viewer, not simply as a man (masculine unreliability in sexual ethics requires no footnote), but as a particular kind of man. Should he lust after her, he is a Turk; should he instead empathize with her plight, a Christian.

--

So much for Orientalism. What of Atlantic slavery?

Much of the volumnious commentary on Powers’s statue(s), then and now, addresses this very question: how does it, how do they, relate to the enslavement of Africans and their descendents in the United States? Did Powers effectively critique American slavery, or, in carving a Greek woman out of snowy marble, did he give white supremacists an easy out?

The discussion played out in texts, but also in a visual register. Multiple artists fashioned African “companions” to the Greek Slave, first in sketch form -

- and then in sculpture (John Bell, The American Slave, 1862).

Amidst such a proliferation of images and texts, Powers’s own motivations recede. For the historian of American culture, the crux becomes the statue’s ability to provoke a range of responses, as if it had taken the nation’s temperature.

For the art historian, a different question arises. Do the visual responses to Greek Slave reform classical art, or do they reject it?

--

We can approach this larger question by first asking: is Powers’s Greek Slave white?

Certainly the statue is carved of white marble. But should that marble also say something about complexion of the woman represented? And if so, are we also mean to imagine her hair, chains, and garments in the same color?

Here again we are posing a question of classical art, not of ancient Greek or Roman, which registered tonal distinctions through application of paints and metals, not to mention variously colored stones.

Classical art, by contrast, posited a strict distinction between form and color. Form was essential, and color applied.

Thus Hogarth, in 1753 (five years before Hamilton’s painting, ninety before Powers’s sculpture), could analyze beauty in a volume printed in black and white.

Note especially the three skinned legs presented, as if on a canvas, at picture left; and compare a passage from Hogarth’s text:

It is well known, the fair young girl, the brown old man, and the negro; nay, all mankind, have the same appearance, and are alike disagreeable to the eye, when the upper skin is taken away: now to conceal so disagreeable an object, and to produce that variety of complexions seen in the world, nature hath contrived a transparent skin, called the cuticula, with a lining to it of a very extraordinary kind, called the cutis.... The cutis is composed of tender threads like network, filled with different colour’d juices. The white juice serves to make the very fair complexion; --yellow, makes the brunnet; ----brownish yellow, the ruddy brown; ---green yellow, the olive; ---dark brown, the mulatto; --black, the negro....

Is this not an egalitarian point of view?

--

So, is Powers’s Greek Slave white? One answer would be, yes, but not because of the marble. Rather, it is the cross that makes her white: not by contrast to the dark-skinned African, but to the heathen Turk.

And yet the argument can be taken further: the cross reveals the marble’s truth. Of course we look at that polished surface and see impossibly fair skin, coursing with white juice.

Here lies one aspect of John Bell’s brilliance:

American Slave does not dissimulate. “Bronze patinated electrotype with silver and gold painting”: bronze for the skin, gold for the earrings, silver for the manacles.

This is entirely in the spirit of ancient sculpture. Is it classical? The question can be answered scholastically, or it can be answered historically. For now let us take the second route. Write Martina Droth and Michael Hatt, who showed it alongside Greek Slave in 2014: “Prior to our exhibition, the two works had never been brought physically together; indeed, The American Slave had never before been lent to a museum either in Britain or the United States.”

--

By way of conclusion, we might step back from Hamilton’s painting and Powers’s sculpture, and ask a more general question: what does classical art do?

The first answer is obvious. It claims ancient Greek and Roman art as the basis of a white, European identity that never existed in antiquity. In so doing, it renders ancient statues retrospectively “white” in a way that would have been incomprehensible to ancient viewers; removes ancient sites from their messy contexts and places them in a togate fantasy.

Classical art achieves this primarily by producing (as a foil to the white European) the figure of the Turk, in whose lands that ancient art exists, but to whom, it is argued, that art does not (cannot) belong. Ancient art becomes the white woman who, “exposed to the gaze of the people whom she abhors,” awaits her salvation by Dawkins and Wood.

The second answer is visually obvious but little discussed. Classical art renders plainly the economic basis of European hegemony, in particular the massive accumulation of wealth enabled by exploitation of unfree, predominately African, labor. It allows that basis to be depicted without censure, indeed even to reverse the charge and cast the Turk as the slave master.

Whereas the economic basis is rendered visible, the psychological, erotic dimension of empire is suppressed (third answer). Classical art seeks to remove the stain from behind Venus’s thigh, claims to empty the skin of its juices, swathes its young adventurers in yards of thickly woven erudition.

To understand classical art as the “reception of antiquity” misses two thirds of the story.

-- January 2019 / May 2020